Outcome 2: Increasing Resilience

There is increased resilience within the landscape for its natural resources, habitats

and species to adapt to the impacts of climate change and other pressures.

- WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

Climate change is having fundamental impacts upon the National Park, with more unpredictable and more extreme weather events. This will lead to changes in landscape, habitats and crops, and increase soil erosion and flooding.

For this outcome our priorities for the next five years are:

- 2.1 IMPROVE SOIL AND WATER

To improve soil and water by reducing soil erosion, improving carbon capture and filtration and reconnecting wetland habitats.

Over the last 50 years there has been a national decline in soil health leading, locally, to erosion and increased sediment and pesticides in our rivers.

Water quality has also declined as a result of increased fertilisers and nitrates from agriculture, roads and sewage, and other chemicals appearing in our water sources.

Climate change and population increases are adding pressure on a limited natural resource, meaning that the South East of England has been designated a region of severe water stress.

At the same time, extreme weather events are increasing flood risk, often exacerbated by the use of nonporous surfacing and changes in vegetation cover.

Increased understanding of land management impact from pilots developed during the last Plan, are being actively used to change practices.

These changes often have multiple ecosystem benefits − for example, the use of winter cover crops can reduce nitrate leaching by 90%, keep nitrogen in the soil for the following crop, provide excellent winter habitat for farmland birds, stabilise soil, add humus and fix carbon.

New initiatives are also underway to scale up the use of natural habitats to alleviate flooding, reconnecting rivers to their floodplains so they can adapt naturally as water levels continue to rise.

Making more room for water will also enable the restoration of wetland habitats such as floodplain meadows, reed beds and marshes, and take the pressure off urban areas.

Example: The Aquifer Partnership (TAP)

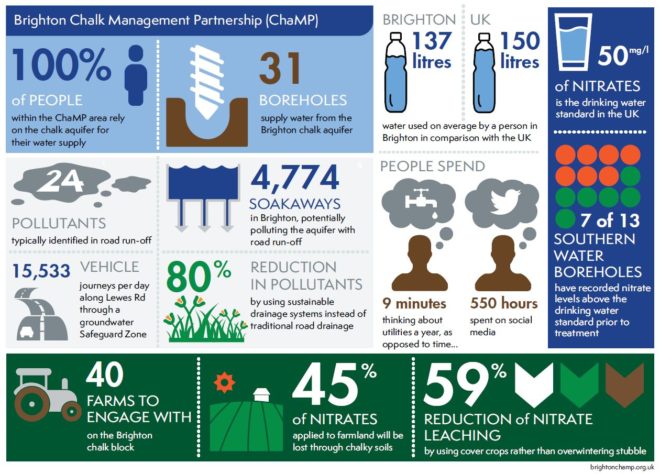

The chalk aquifer of the South Downs stores drinking water for 1.2 million people in the south east and feeds local streams and rivers.

But, like many aquifers and rivers across the world, it is polluted with nitrates – from fertilisers, manure heaps and road run-off.

TAP aims to protect and improve the quality of groundwater in the Brighton Chalk, to ensure it remains a sustainable resource for public water supply.

In addition interventions have benefits for soil health and wildlife. TAP provides practical advice and improvements to land management in the urban and rural area.

It undertakes research to increase knowledge of the issues and to monitor success, through a series of trials for different types of interventions.

- 2.2 IMPROVE TREES AND WOODLAND

To improve the resilience, quality and quantity of trees and woodlands in the National Park, and ensure that the right tree is planted in the right place.

Over one-fifth of the National Park is woodland. This locks up thousands of tonnes of carbon, slows water flows, provides valuable habitat and is a sustainable source of home grown timber.

The good news is that these multiple benefits are now better understood, the need for action is well integrated into national policy, and there is also better scientific data available to help those who are managing and planting trees.

But, as with all habitats, our trees and woodlands are under an unprecedented threat from the effects of climate change, damage from browsing animals pests and disease and poor management.

In the National Park a wider range of species and provenances will be used to increase resilience, creating greater diversity of age structure within our woodlands and creating conditions for woodlands to regenerate naturally so they can evolve with the changing climate.

Careful, targeted planting of new trees able to adapt, thrive and enhance their urban or rural surroundings, will also be used.

Example: Bringing Back Elm

English elm was an iconic landscape tree, provided hard, rot resistant timber, and was an important habitat for key species such as the white letter hairstreak butterfly.

English elm was an iconic landscape tree, provided hard, rot resistant timber, and was an important habitat for key species such as the white letter hairstreak butterfly.Dutch Elm Disease has almost destroyed English elm populations across the UK landscape, killing an estimated 60 million trees since its outbreak in the late 1960s.

Parts of the eastern Downs and Brighton & Hove are the last remaining refuges for mature English elm. In recent years, elm breeding trials in America and the continent have successfully reared highly resistant cultivars of elm.

The project seeks to raise awareness of these and to facilitate the growing of more suitable cultivars to bring elms and the wildlife that relies on them back to the National Park.