Celebrating the amazing rivers of the South Downs National Park

September 19, 2019

The South Downs is internationally-renowned for its quintessentially English countryside, pretty chocolate-box villages and stunning white cliffs.

Less well known is the complex network of waterways that crisscross this national gem.

The National Park’s rivers and all their tributaries are the life-giving arteries of the ecosystem, supporting an incredible variety of plant, fish, bird, amphibian and insect species. For this very reason river health remains a key priority of the National Park Authority, which has been working with landowners, farmers, key stakeholders and visitors to encourage good river management and reduce polluting run-off.

To mark World Rivers Day on September 22 we go on a tour of the South Downs’ rivers and shine a light on their murky depths – as well as giving our tips for wildlife watching!

Cuckmere, East Sussex

A small lowland river that arises in the Weald but dramatically cuts through the South Downs past the Long man of Wilmington, the picturesque village of Alfriston, the high and over white horse before reaching the sea at Cuckmere Haven at the Western end of the Seven Sisters white cliffs. The Cuckmere is the only undeveloped estuary in South East England although the river was straightened in the Victorian era so boats (mostly smugglers) could navigate to Alfriston.

A small lowland river that arises in the Weald but dramatically cuts through the South Downs past the Long man of Wilmington, the picturesque village of Alfriston, the high and over white horse before reaching the sea at Cuckmere Haven at the Western end of the Seven Sisters white cliffs. The Cuckmere is the only undeveloped estuary in South East England although the river was straightened in the Victorian era so boats (mostly smugglers) could navigate to Alfriston.

This has left the dramatic meanders cut off from the river.

Look out for: The undeveloped estuary and surrounding marshes attract a wide variety of wetland birds, especially on migration and in the winter months. Spot a Redstart, unusual wading birds, Little Egrets and flocks of Wigeon and Lapwing.

Ouse, West and East Sussex

The River Ouse Corridor covers over 140 miles of waterways and is an important wildlife haven. The headwaters of the Sussex Ouse rise on the Ashdown Forest, whilst two of the lower tributaries, the Bevern and Northend Streams are derived from springs rising in the chalk of the South Downs. They then continue their journey over greensand and clay in their lower sections before returning to the Valley thorough the Downs from the village of Hamsey. The River from this point is tidal as it passes through the historic town of Lewes and on to the sea at Newhaven.

The River Ouse Corridor covers over 140 miles of waterways and is an important wildlife haven. The headwaters of the Sussex Ouse rise on the Ashdown Forest, whilst two of the lower tributaries, the Bevern and Northend Streams are derived from springs rising in the chalk of the South Downs. They then continue their journey over greensand and clay in their lower sections before returning to the Valley thorough the Downs from the village of Hamsey. The River from this point is tidal as it passes through the historic town of Lewes and on to the sea at Newhaven.

The floodplain below Lewes, known as the Lewes Brooks, supports a diversity of plant life including water crowfoot and starwort and a wide range of aquatic invertebrates. In winter these floodplains also support important populations of wintering birds.

Look out for: Brown and migratory Sea trout ascend each year to their spawning grounds in the gravel beds of the tributaries. Lapwing, redshank, little grebe, cormorant, reed bunting and reed warbler are common, while there is a chance of seeing a short-eared owl in the winter.

River Adur, West Sussex

The River Adur begins as two separate branches in the Sussex Weald which meet at Henfield before flowing on through the South Downs past Upper Beeding and Lancing College. As with the Ouse there are some tributaries that arise as chalk springs and these are good for a range of wildlife including spawning trout.

The River Adur begins as two separate branches in the Sussex Weald which meet at Henfield before flowing on through the South Downs past Upper Beeding and Lancing College. As with the Ouse there are some tributaries that arise as chalk springs and these are good for a range of wildlife including spawning trout.

Below Upper Beeding the river is tidal and has large areas of saltmarsh habitat. This is one of only two areas of saltmarsh along the South Coast between between Chichester and Sandwich in Kent, with a good diversity of plants such as sea purslane, sea lavender and golden samphire.

The Adur continues to the coast at Shoreham, a busy port and harbour.

Look out for: Wading birds, including a nationally-important winter population of Ringed Plovers.

River Arun, West Sussex

The River Arun flows from the High Weald close to the town of Horsham south through the heart of West Sussex, joining with the Rother at Pallingham. From here the river becomes tidal as it continues south through the picturesque Arun Valley, through the chalk downs and past historic Arundel with its dramatic castle. The Arun then continues through the coastal plain to the sea at Littlehampton.

The River Arun flows from the High Weald close to the town of Horsham south through the heart of West Sussex, joining with the Rother at Pallingham. From here the river becomes tidal as it continues south through the picturesque Arun Valley, through the chalk downs and past historic Arundel with its dramatic castle. The Arun then continues through the coastal plain to the sea at Littlehampton.

The Lower Arun contains the most important wetland site in the National Park – the freshwater wetlands at Pulborough, Amberley and Waltham Brooks. These sites are designated SSSI, SAC and SPA, under the European Habitat directives. The area has a rich native flora of marshes, ditches and lowland bog and associated invertebrates, including the rare Ramshorn snail.

Look out for: In winter the area is important for wildfowl and wading birds, including the Bewick’s Swan. The Lower Arun is also famous for water voles.

River Rother, Hampshire and West Sussex

The Western Rother rises close to the Hangers near Selbourne, initially as a chalk stream. As the river moves east past the town of Petersfield it moves into the greensand and clays of the weald where it undergoes a major change with large amounts of sediment in the river and its tributaries. Many of the tributaries have hammer ponds – structures that were constructed to provide water to the early iron industry. Along the middle stretch of the river the sandy soils are used for growing high value salad and vegetable crops, with the river an important source of irrigation in the summer months. There also many old water mills along the river, remnants of a more industrial past.

The Western Rother rises close to the Hangers near Selbourne, initially as a chalk stream. As the river moves east past the town of Petersfield it moves into the greensand and clays of the weald where it undergoes a major change with large amounts of sediment in the river and its tributaries. Many of the tributaries have hammer ponds – structures that were constructed to provide water to the early iron industry. Along the middle stretch of the river the sandy soils are used for growing high value salad and vegetable crops, with the river an important source of irrigation in the summer months. There also many old water mills along the river, remnants of a more industrial past.

In the lower river the floodplains have been separated from the river by the construction of embankments to aid navigation as far as Midhurst. Traditionally these meadows would have collected silt in the winter floods and provided fertile conditions for the local populations that farmed them.

The Rother is still a good area for fish and many fishing clubs fish the waters.

Look out for: Otters have recently been recorded returning to river. Kingfishers and grey wagtails are also common sights. In spring look out for the rare clubtail dragonfly.

River Meon, Hampshire

The Meon is a rare and precious habitat. It is a chalk stream, fed almost entirely by springs rather than by rain, and supports a unique ecology. Less famous and smaller than the Rivers Test and Itchen, it is a more ‘natural’ river, with fewer modification made by man and has more energy due to its steeper gradient.

The Meon is a rare and precious habitat. It is a chalk stream, fed almost entirely by springs rather than by rain, and supports a unique ecology. Less famous and smaller than the Rivers Test and Itchen, it is a more ‘natural’ river, with fewer modification made by man and has more energy due to its steeper gradient.

The river rises near East Meon and flow south-westwards for 21 miles through the Meon Valley before emptying into the Solent estuary at Titchfield Haven.

For over half its length the river flows over the permeable chalk of the South Downs, with a visible change of character at Holy Well, near Wickham where the underlying geology changes to impermeable Reading Beds and London Clays.

The waters of the river and the chalk aquifer have been important to people for thousands of years and are an integral part of the culture of the valley and contemporary life. In 1086, there were already 33 mills on the river and remains of water meadow systems dating back to the 1600s can still be seen today. The Isaak Walton pub in East Meon is testament to the trout fishing interest on this river that is still evident.

Chalk streams are identified as priority habitats under the European Habitat Directive and the UK Biodiversity Action Plan.

Look out for: Species found on the river include otter, as well as fish such as bullhead, brook lamprey, the beautiful plant water crowfoot, and the majestic kingfisher, as well as more recent additions such as egrets.

River Itchen, Hampshire

The River Itchen is one of Britain’s premier chalk rivers. Fed by the chalk aquifer of the South Downs and North Hampshire the waters are often crystal clear.

The River Itchen is one of Britain’s premier chalk rivers. Fed by the chalk aquifer of the South Downs and North Hampshire the waters are often crystal clear.

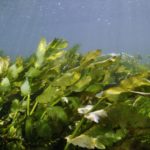

Much of the river is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest and international Special Area of Conservation AC for its rich wildlife. In summer the waters have an abundance of water crowfoot and river invertebrates and this in turn supports a rich fish life including brown trout and brook lamprey.

Look out for: Water voles and otters are often sighted and the river is also home to the rare native white-clawed crayfish.